Our mother languages: What’s in it for us?

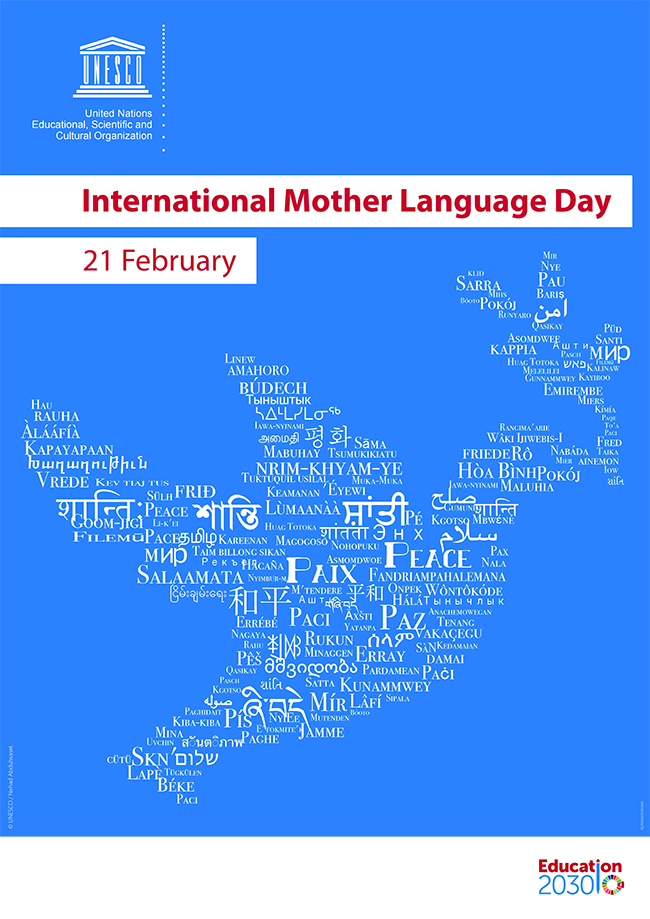

At the SU Language Centre, we share UNESCO’s belief in the importance of cultural and linguistic diversity for sustainable societies, and we embrace the world-wide celebration of International Mother Language Day on 21 February each year.

Mother Language Day is not only about your and my individual mother languages, but also about those of the people around us. If we understand that the mother language of the person next to us is just as dear to them as our mother language is to us, and respect that, we’ve made great strides already.

Why are mother languages important, other than because we attach emotional value to the language(s) we grew up with and started expressing ourselves in? How can they be of practical use to us, even if we often function in a second or third language to ensure that we communicate in a manner that helps others to understand what we’re saying?

Mental springboards

Mother languages are mental springboards. We all use our mother language as a way to scaffold knowledge. When you acquire new knowledge, you usually start with familiar information and then journey from there into the valleys of unknown knowledge. So, if you start at a place where you know what a certain concept is in your mother language, you have somewhere to kick in your heels and get purchase, and you can use that familiarity as a springboard from where to understand more complex concepts, even when offered in a different language than your mother language.

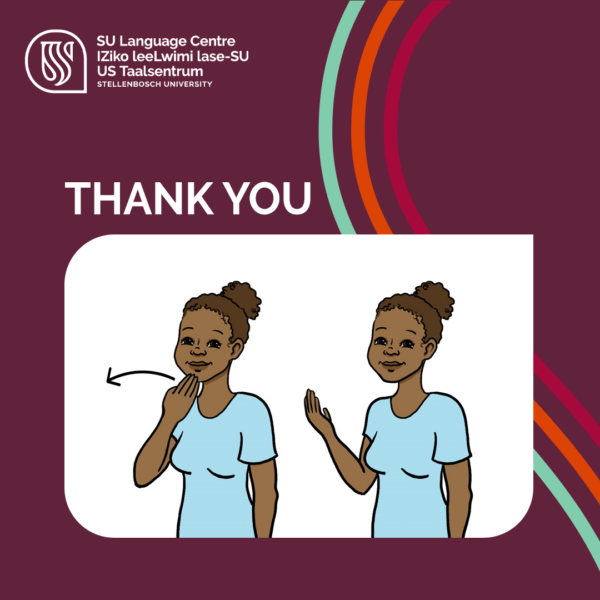

Therefore, students can, and should, use their mother languages at university, even if their language is not one of the official learning and teaching languages of the institution. If we think of SU, the University has committed to using English, Afrikaans and isiXhosa – the official languages of the Western Cape. Afrikaans and English are the primary languages of learning, teaching and assessment. IsiXhosa may also be used in learning and teaching, where there is capacity and lecturers find it appropriate to use it, and where there is a pedagogical need. The University is committed to developing isiXhosa as an academic language, as well as to maintaining Afrikaans as a language of teaching, learning, assessment and research. SU is also one of the few South African universities aiming to develop and promote South African Sign Language. This is all part of a national mandate for tertiary institutions to adopt at least one African language, where we focus our resources on that language, while at the same time maintaining what we’ve already developed. This is an important way for us to bring the South African Constitution to life. By respecting languages at a tertiary level, we raise their status.

SU students and staff are indeed a far more diverse bunch than only English, Afrikaans and isiXhosa speakers, but working with the most common mother languages in the Western Cape is a starting point. And other South African universities have committed to develop at least one of the official South African languages in their regions. This way, speakers of isiZulu could, for example, also benefit from resources in isiXhosa, as those languages are closely related, and the same applies to other closely related languages. But we as mother language speakers need to choose to use our languages ourselves when the opportunity arises.

Raising the status

If we want to maintain, extend and raise the status of our languages, there are two overarching ways to do it. One way is by writing in that language – through the creation of literature – showing that your language is capable of expressing abstract thought and creative and complex ideas, and that it is flexible enough to do so. The second way is through creating terminology to describe new technical domains.

Probably every single language apart from English (as terminology seems to be created in English far more naturally as part of the process of new inventions and developments) needs to continually raise its status to keep up in our modern world. Every other language, whether French, German, Chinese, Afrikaans or isiXhosa, has the challenge to try to keep pace, and English itself doesn’t even always stay ahead! Also, English might possess the terminology, but the meanings of those words are not always so transparent. Terminology in isiXhosa, Afrikaans or even French is often much more descriptive and therefore more transparent to the speakers of that language. Think of “koppelaar” in Afrikaans for “clutch”, or the isiZulu word for “bill”, “umthethosivivinywa”, literally “a law in process”. There are so many other examples. But do we choose to embrace and use those beautiful words, or do we revert to English automatically?

A great benefit of raising the status of a language and using various languages is that we make our environments more inclusive. Seeing and experiencing their languages in different spaces remind people that they are part of something bigger than themselves.

Different sides of the same coin

As we celebrate Mother Language Day this year, perhaps we should start pondering the following two questions: What does your mother language do for you, and what do you do for your mother language? When you use your mother language for learning, in everyday life and in official matters, you’re not only helping yourself but also supporting and preserving your language’s heritage. Your use of the language keeps it alive and ensures it continues for the future.

And then, when we take another step forward, namely to start learning each other’s mother languages, we support and strengthen those languages even more, while finding new ways to understand and appreciate each other.

– by Susan Lotz, Dr Kim Wallmach, Sanet de Jager and Jackie van Wyk