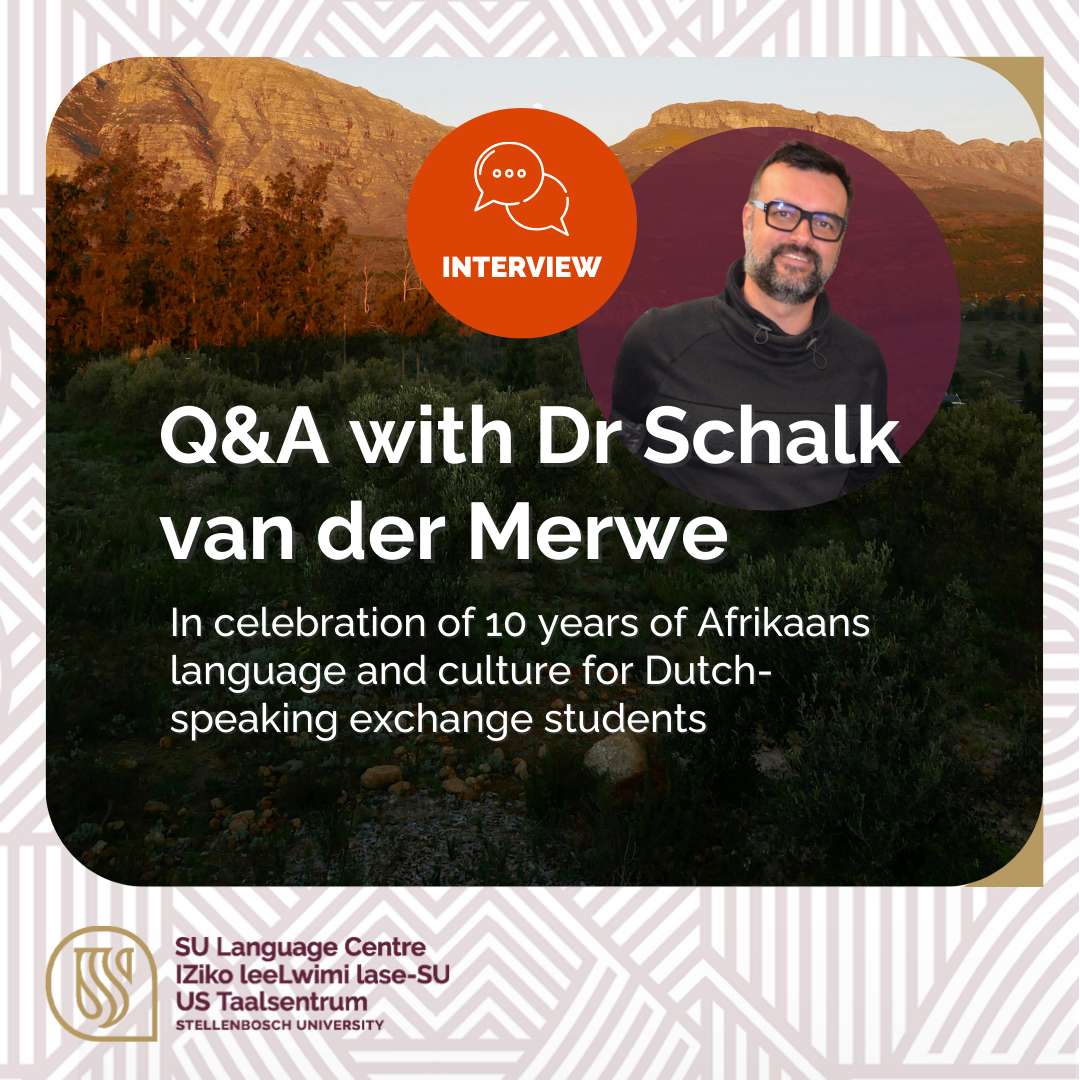

Q and A with Dr Schalk van der Merwe in celebration of 10 years of Afrikaans language and culture for Dutch-speaking exchange students

Dr Schalk van der Merwe, extraordinary senior lecturer at Stellenbosch University (SU), is a published author and an experienced bass guitarist. He balances his academic career with his work as a professional musician and often draws on his own musical experiences to enrich his research. He taught history at SU from 2005 to 2017, with a focus on African history. Since 2019, he has been involved in the University’s International Office, where he teaches in various fields, ranging from South African political history to popular culture and identity.

In his doctoral research, which he completed in 2015, he examined the political and cultural dynamics of Afrikaans music from early in the 20th century up to the post-apartheid era.

That study led to his book, On Record: Popular Afrikaans Music and Society, 1900–2017, which covers themes like Afrikaner nationalism, censure during apartheid, class differences and racial politics on the post-apartheid pop music scene. Van der Merwe has contributed to various academic publications, including Fuck off! Fokofpolisiekar’s Afrikaans Punk in the Postcolony and Ghosts of the Popular: The Hidden Years Music Archive and the Interstices of South African Popular Music History (with Lizabé Lambrecht).

He has been a regular guest lecturer at the Afrikaans language and culture course for Dutch-speaking students for several years, where he shares and discusses key events from South African history with students in a narrative style. As part of the 10-year celebrations of the course, we asked him a few questions.

Schalk, you offer two courses at Stellenbosch International as part of the Global Education Programme. Please tell us more about these courses.

The one is Overview of South African History, which is an exploration of the important themes in our history, from the first people to the Government of National Unity (GNU). The other course is South African Popular Culture and Identity, which is more interdisciplinary, and explores, for example, how the intersections of language, race and culture are expressed in cultural practices. We quite often listen to music in class, from hip-hop, kwaito and amapiano to Afrikaans pop music. We also look at things like sites of memory, with specific reference to Sophiatown and District Six.

You have been a regular guest for about three years at the Afrikaans language and culture course, where you present a guest lecture that focuses on an overview of the history of South Africa. In your opinion, what is the relationship between history and origins when it comes to the formation of a specific culture and identity? Why, do you think, can one form a better understanding of a culture by learning more about the history of that culture?

It feels like I’ve been involved much longer! Oh, I think the two go hand in hand. Narratives like ‘who I am/who we are’ are formed in, and in reaction to, specific historical circumstances. One has to understand these circumstances if you want to understand culture and identity. A good local example – and South Africa has an abundance of such examples – is the development of an Afrikaner national identity (that is, their identity as a volk) and the concomitant Afrikaner culture. The way in which most of us interpret/understand these terms was never a given outcome. The idea of a ‘volk’ was deliberately created under the banner of Afrikaner nationalism as it took hold in the politics of the early twentieth century. There were other ideologies going around as well, but they started having less influence as time went by. The fact that so much was invested in, particularly, white Afrikaans school curricula primarily focused on national identity was instrumental in its fairly robust continued existence today.

Dr Van der Merwe with exchange students from Belgium and the Netherlands in the Afrikaans language and culture for Dutch speaking students course in 2017.

What would you say are the most important aspects of our complex history that international students should understand – particularly as far as the history and origins of Afrikaans-speaking people are concerned?

When I work with international students – who mostly come from Europe – it is important to take care to explain colonialism and its consequences to them. They do not come from colonial and post-colonial worlds. In their world, the construction of, for example, race is not such a central historical factor, whereas it is a core element of the history of South Africa. As far as the history and origins of Afrikaans is concerned, it is essential to portray the language’s diversity, as well as how it was utilised in service of social change. I usually highlight the slaves’ influence to clarify the development of the language and its cultural elements that are still visible today. The fact that Afrikaans came into existence in unique circumstances and that it is one of only four languages that were standardised in the twentieth century are also important talking points. Finally, I feel that, for a young language, Afrikaans has already seen a lot of life. It has been a language of conflict and a language of oppression, but also one of protest and hope. The Afrikaans literature is rich, and the realms of the Afrikaans imagination are deep and beautiful.

Finally, I feel that, for a young language, Afrikaans has already seen a lot of life. It has been a language of conflict and a language of oppression, but also one of protest and hope. The Afrikaans literature is rich, and the realms of the Afrikaans imagination are deep and beautiful.

Dr Van der Merwe (left) with course lecturer Helga Sykstus (second from left) and a group of students from Belgium and the Netherlands at the ‘Eet Kreef Herleef!’ concert at Woordfees, 2022.

– by Helga Sykstus